Hating New Things

Vanity, obscenity, running up hills, running out of time, and what Mortal Kombat looked like in the 1850s.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1493, an Italian friar who looked and dressed like the grim reaper managed to convince a large swath of the Florentine population that the world was about to end. You wouldn’t think they’d buy into this — compared to the average European city at the end of the 15th Century, Florence was doing pretty great — but he promised its citizens that, by following his lead, they could do more than just forestall the apocalypse—they could also become richer and more powerful than ever before.

How could they say no?

That Italian friar’s name was Girolamo Savonarola. He was 45-years-old, and, like everyone in their mid-40s, he hated the way the world was changing. He despised the vain and shallow manner of young people. He was disgusted by all the flashy, superficial art he was seeing everywhere (apparently no one pointed out to him that he was living through The High Renaissance). So Savonarola — a social influencer with tens-of-thousands of loyal followers — started a campaign to destroy all the “artefacts of vanity” that were corrupting the culture. He roamed through the city with his crew (who dubbed themselves The Weepers), gathered up all the sinful objects they could find — books, paintings, sculptures, musical instruments, dresses, hats, makeup, mirrors, chess sets, dice, decks of cards — and brought them to the Palazzo Vecchio, where they were tossed into a huge fire. Sandro Botticelli even showed up and threw a couple of his canvases into the flames (not any of his good ones, though).

They called this the Bonfire of the Vanities, and many Florentines loved it. They must have hated the way the world was changing, too.

Screentime

I’VE SPENT AN UNCONSCIONABLE AMOUNT OF MY LIFE in front of a screen, watching things, and I suppose I must accept that this is my preferred method for engaging with the world (as opposed to, say, actually engaging with the world). When I was twelve, I got a small television for my bedroom, a 14-inch screen so small you could practically see the individual pixels flashing, and I spent much of my abundant free time staying up late to watch and rewatch, unsupervised, every new thing I could get my hands on. R-rated thrillers like Silence of the Lambs, Se7en, Reservoir Dogs, Bad Lieutenant; high-end art-flicks like Howard’s End, The Piano, Fargo, Short Cuts; dumb comedies like Ace Ventura and Tommy Boy, and, of course, whatever Zalman King softcore skin-flicks I could tape off cable. I watched it all.

I watched old movies, too — Failsafe, 12 Angry Men — but the movies I really connected with, that seemed to be teaching me something about the world (even if that world was Edwardian Britain at the beginning of the 20th century) shared one thing in common: they were all new.

I used to love new things. I used to anticipate them. But now I hate them. Recency has become a detriment in choosing what I read and watch and listen to. All these new shows and new movies, all this new content one must absorb to remain at pace with pop culture—none of it seems worth my time. Even the good stuff. Even the really, really good stuff. New films can’t thrill me like the films of my youth. How could they?

One of the movies I watched relentlessly in my youth was the action thriller In The Line of Fire, in which Clint Eastwood is an enfeebled secret service agent sparring with an assassin played by John Malkovich (this, a decade before Malkovich went full Malkovich). Payphones play a vital role in the film. So do print-outs from dot-matrix printers. These meagre details meant something to me: I borrowed quarters to call home from payphones; I ripped perforated strips off my printed-out book reports. I came from this world; its tectonic pressures formed me. And now, with every new movie, every new show, every new meagre detail that I don’t recognize, the place I came from is diminished. New things push aside old things until eventually the old things are meaningless. I have become an old thing, too, and am likewise diminished.

Maybe this is how Girolamo Savonarola felt in the 1490s.

Trying (and Failing) to Live in The Past

IN THE PAST FEW YEARS, in my prejudice against newness, I’ve made a conscious effort to consume more old things and fewer new things. I seek a more balanced media diet; an attempt to be temporally omnivorous. And because I track everything I read and watch, I can quantify whether or not I have been successful.

Here is a breakdown of the books, films, and TV shows I have consumed so far this year.

I claim to hate new things—but look! I have read and watched more things from the last three years than I have from the past thousand. Despite my active resistance, I cannot escape new things.

The music world, however, seems to be having the opposite problem: they cannot escape old things.

When Old Things Become New Things

THIS PAST SPRING, Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” — a song that was released thirty-seven years ago — hit #3 on the Billboard Hot 100 (with a little bit of help from Max Mayfield). According to the latest streaming data, people are listening to more old music than new music. Spotify recently reported that a third of the tracks on their weekly global charts are at least 18 months old. According to some sources, old songs now represent 70-percent of the U.S. music market.

This is what I want, right? For old things to be granted an extended lifespan, for them to remain perpetually relevant? (And, through my association with them, to remain perpetually relevant, too.)

In his essay “Is Old Music Killing New Music?” Ted Gioia argues that this trend towards old things is inhibiting up-and-coming artists, stifling innovation, and thwarting the creation of the new things that will someday become the old things our children will cherish.

“Never before in history have new tracks attained hit status while generating so little cultural impact. In fact, the audience seems to be embracing the hits of decades past instead. Success was always short-lived in the music business, but now even new songs that become bona fide hits can pass unnoticed by much of the population…plenty of exceptional young musicians are out there trying to make it. They exist. But the music industry has lost its ability to discover and nurture their talents.”

At the same moment in history—

—that Girolamo Savonarola was burning up everyone’s stuff, Leonardo Da Vinci was a few hundred miles away, in Milan, putting the finishing touches on a new mural. Maybe adding a little shade to the bread rolls. Maybe tweaking the angle of Thomas’ finger to make it look more doubtful.

Years earlier, when Da Vinci first laid eyes on the surface he was meant to paint, he himself was filled with doubt. A fresco? On that shitty wall? The surface was crumbling and damp, the paint wouldn’t stick, the colours were dull and lifeless. “There’s no way I can do this,” Da Vinci said.

But then, of course, he did it.

He called that fresco “The Last Supper”—it took him three years to complete.

It took me—

—eleven years to write my first book. It was published in 2016.

It’s almost 2023, and I’m still not finished the next one.

Fuck That Shit: Part I

THIS PAST SUMMER, I took my kids — aged four and eight — to a country fair. As we strolled through the midway, scoping out the ring toss, appraising our chances of winning a stuffed dragon, a song was playing from a nearby speaker, loud enough to be heard over the roar of whipping-around rides and their screaming passengers.

The lyrics went something like this: “Hold on, hold on, fuck that / Fuck that shit / Hold on, I got to start this motherfuckin' record over again / Wait a minute / Fuck that shit / Still on this motherfuckin' record / I'ma play this motherfucka for y'all.”

I was shocked, but only briefly, and mostly on behalf of the parents and small children who were wandering alongside us. The truth is, my kids had heard that song before.

Fuck That Shit: Part II

MINE WAS THE GENERATION that grew up in the midst of the great moral panic about profanity in music. One of the defining symbols of my childhood was the Parental Advisory label they began sticking to CD cases in the summer of 1990. Parents (Tipper Gore, at least) were worried about the deleterious moral effects pop music’s increasingly “explicit content” might have on their children. But to those children, that sticker was a symbol of oppression. To be told what you could and couldn’t listen to was the real moral crime, not whatever bit of profanity and sexual innuendo the label was theoretically protecting you from.

Thirty years later, those fair-minded free-speech-loving children are parents themselves. And what do they think, now, about explicit lyrics in music?

We don’t think about it. I don’t, at least. Hearing that song at the fair, out in public, among other people’s children, made it seem offensive. But in the privacy of our home, those fucks and shits have no power. One of the first songs my daughter and I danced to — back when she was just a few months old and our “dancing” was just a slightly faster version of the lullaby sway we did at bedtime — was Iggy Azalea’s “Fancy” which opens with this verse:

You should want a bad bitch like this (ha?)

Drop it low and pick it up just like this (yeah)

My daughter, now eight, has rediscovered this song (it was number one on the Billboard charts the day she was born, and therefore her “birthday song”). We often listen to it on the drive to school.

A strange thing has happened since I became a parent, which I think is true of many parents of my generation: we’ve become more anxious about how our kids are receiving content than the content itself.

Oh, the strange contradictions of parenthood! I’ll let my kids listen to these filthy songs, but I won’t let them watch YouTube or play video games on a tablet.

Me, the kid who grew up with a TV in his bedroom.

What a Wicked Game You Play

THE OTHER MORAL PANIC of my youth was about video games. Specifically, a game called Mortal Kombat in which you punched and kicked and sometimes pulled the spinal column out of your opponent’s body. Today, parental anxieties about video games like Fortnite are less focused on the game’s central premise — killing other players with axes, grenades, and high-powered rifles — than they are on the problem of screentime itself.

Here’s a quote from a recent article in The Scientific American about the damaging effects that video games are having on the youth of today:

“Playing does not add a single new fact to the mind; it does not excite a single beautiful thought; nor does it serve a single purpose for polishing and improving the nobler faculties. Those who are engaged in mental pursuits should avoid it as they would an adder’s nest, because it misdirects and exhausts their intellectual energies. Rather let them dance, sing, play ball, perform gymnastics, roam in the woods or by the seashore.”

I tend to agree with the spirit of this article. It raises some really interesting points, don’t you think? There’s only one problem—

—this article isn’t about video games. And it isn’t recent. It was written in 1859, and it’s a warning against the pernicious influence of chess.

“It is a game which no man who depends on his trade, business or profession can afford to waste time in practicing; it is an amusement — and a very unprofitable one — which the independently wealthy alone can afford time to lose in its pursuit.”

Chess was hardly a new thing in 1859, but the way people had started playing it in the middle of the 19th Century — competitively, in tournaments — turned chess from a drawing room board game into a major international sport. It was an old thing, but people were doing it in a new way. Apparently The Scientific American didn’t like that.

“Chess is a mere amusement of a very inferior character, which robs the mind of valuable time that might be devoted to nobler acquirements, while at the same time it affords no benefit whatever to the body…those who have becomes the most renowned players seems to have been endowed with a peculiar intuitive faculty for making the right moves, while at the same time they seem to have possessed very ordinary faculties for other purposes.”

Today, parents compel their kids to play chess for the exact opposite reason: to build their brains, develop problem-solving skills, hone their concentration, prepare them for the intellectual struggle of their future professional lives. But is chess really that different than playing video games? The isolation, the concentration, the necessary obsession required to master it?

Chessboards, you’ll remember, were among the artefacts of vanity set ablaze by Girolamo Savonarola and his pals.

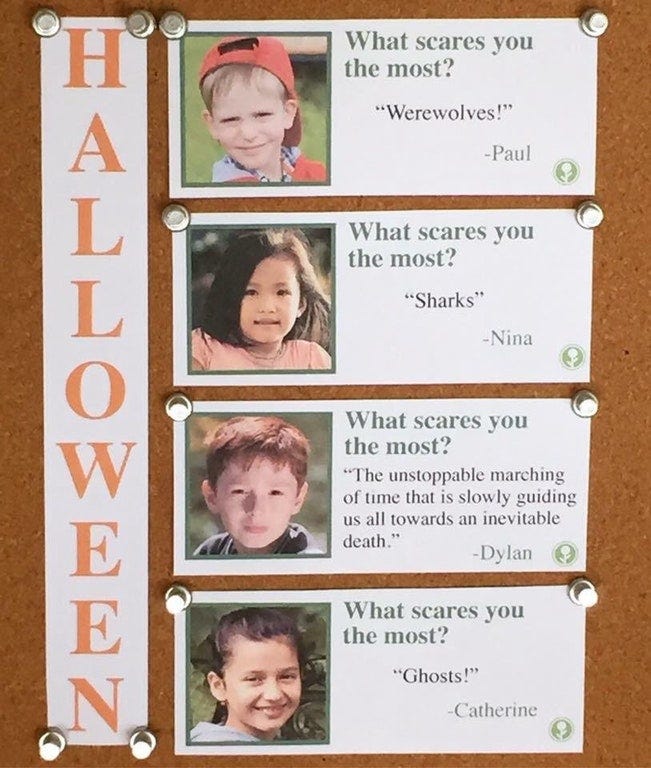

The Unstoppable March of Time

TIME IS RUNNING OUT. Everyone knows it – mathematically, temporally – but you only begin to feel how quickly time is running out when you’re on the downward arc of your life. Current average life expectancy for a male of my economic and cultural background is 81.15 years, which means I’m already two years past the midpoint of my life. Downward arc might sound grim, but think of a plane landing, the soft descent, the pleasant earthward float, the jarring bump, the heave of the brakes. It seems scary, but to arrive anywhere – even death – is perhaps a relief. Life is over, fun is over, but so is everything else: like, for example, worrying about time running out.

Maybe that’s why the time I spend in front of the television, now, feels like such a waste: because it is. It’s not the diminishing value of new things, but the diminishing days I have left. Watching movies in my bedroom at the age of twelve, I was learning something about the wider world that awaited me. It was exciting, all the possibilities, all the places I might go, all the things I might be. But I’m living in that world, now, and it’s hard not to see all these new things as artefacts from the lives I haven’t lived, the places I haven’t been, the people I didn’t become.

Epilogue

A FEW YEARS AFTER his infamous bonfire of the vanities, Girolamo Savonarola was excommunicated by the church, arrested, imprisoned, tortured, and eventually confessed (twice!) to having fabricated his prophecies about the world coming to an end. He was condemned as a heretic, hanged and (somewhat ironically) burned in a bonfire. His ashes were later tossed into the Arno River.

Today, the Italian High Renaissance is considered one of the most exceptional periods of artmaking in human history. The artists who flourished during that era are still remembered today. But do they loom large in our cultural memory because their work is still relevant? Or do their names remain on the tips of our tongues because a new thing came along to help us remember them?

Hard to say.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed reading this particular issue of TOLSTOYAN, you can share it with a friend by clicking the button below.

If you don’t already subscribe, and would like TOLSTOYAN delivered directly into your inbox on the 23rd of each month, click the button below to subscribe.

I’d love to hear all about the new things you hate and the obscene songs you’ve played for your children. You can get in touch by responding directly to this email, or by clicking the button below to leave a comment.