The Plague Year

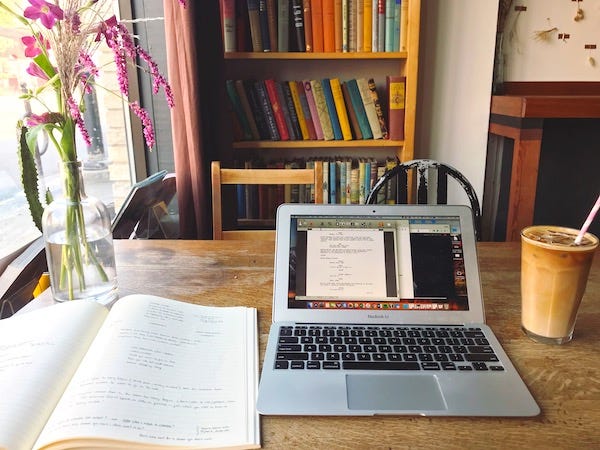

The desk in the front window of Black Squirrel Books in Ottawa, with an iced latte (in the Before Times).

2020 was everything, all at the same time. Boring and busy, restful and exhausting, completely harrowing and kind of wonderful. It was eventful and uneventful: everything seemed to happen, except for all the things that couldn’t. It was unlike any year before—except for all the other years of existential crisis humanity has precariously navigated (then promptly forgotten about).

I wrote more in 2020 than any year before. And I published virtually nothing. A victory for daily toil, a failure of professional achievement. I made progress on some ambitious projects: finished a few, lost faith in others; put one thing in a drawer and started a new one; crawled over the finish line and proceeded at light speed towards another before tripping over my feet. Maybe not a total failure. Let’s call it a draw. There’s a chance yet that some of these things might yet become something. We’ll see.

Maybe that’s the best mantra with which to consider the paradox of 2020: we’ll see.

////

In 2020, I often found myself escaping the present by looking backwards into the past. There’s a word for this, it turns out (and of course it’s a German compound word): ruinensehnsucht, a longing for ruins, which was coined to describe European travelers in the eighteenth century who visited places like Corinth, Thebes, Mycenae, etc, to gaze upon the once glorious architecture now crumbled and decayed. Stendhal called ruin-gazing: “The most intense pleasure that memory can procure.”

Hubert Robert, View of the Grande Galerie in Ruins, 1796, oil on canvas (Louvre Museum, Paris, France)

“Beholding old stones, we may feel our anxieties over our achievements – and the lack of them – slacken. What does it matter, really, if we have not succeeded in the eyes of others, if there are no monuments and processions in our honour or if no one smiled at us at a recent gathering? Everything is, in any event, fated to disappear…Judged against eternity, how little of what agitates us makes any difference.”

This quotes comes from Status Anxiety by Alain de Botton, which was, appropriately, the last book I read in 2020. Not only is it a good primer on the history of capitalism and how its principles (most notably wealth = virtue) became the foundation of modern civilization, but it’s also a low-key condemnation of meritocracy and individualism, those twin ideals that seem really great in theory, but which, in political practice, are the source of virtually all our angst and anxiety and dark impulses.

“If the successful merited their success, it necessarily followed that the failures had to merit their failure. In a meritocratic age, an element of justice appeared to enter into the distribution of poverty no less than that of wealth. Low status came to seem not merely regrettable, but also deserved.”

De Botton makes the point that our assumptions about a person’s “success” are deeply flawed. It is very likely that a housecleaner living just above the poverty line, in a small apartment she shares with others, is living a much richer, more fulfilling, more influential life – is ultimately more “successful” – than your average upper-middle-class suburbanite with two cars and a cottage and an Instagram feed full of bathroom selfies and vacation pics. But it’s hard (maybe impossible) for us to see beyond the markers of status the last three centuries of capitalist ideology have coded into our genetics.

We can’t see another’s interiority, just the things they have acquired. An old idea, I guess, but one that Status Anxiety offers an edifying new perspective on.

/////

I took great comfort, this year, in perspectives like this. The practice of meditation is sometimes described using the metaphor of a passing train: if you are standing right next to the tracks, the train will seem to be moving at an incredible speed, blurring past, roaring, whipping the air, it’s total chaos, you can’t get a clear look at it. But if you step backwards, away from the tracks, you’ll see more of the train, it will seem to slow down. And if you continue stepping backwards, you’ll eventually reach a point where you can see the entire thing from engine to caboose, it’s no longer blurry, no longer roaring; you can count the cars and read the words stenciled on them. It all makes sense.

This process of stepping away from the tracks is meant to represent the act of meditation, but it’s also an accurate description of what it feels like to read (and think) about history in a year like this. Looking back, I can see now that the toughest weeks of 2020 were the ones where I was stuck entirely in the present, standing right beside the tracks, trying to read the fine print on the passing cars.

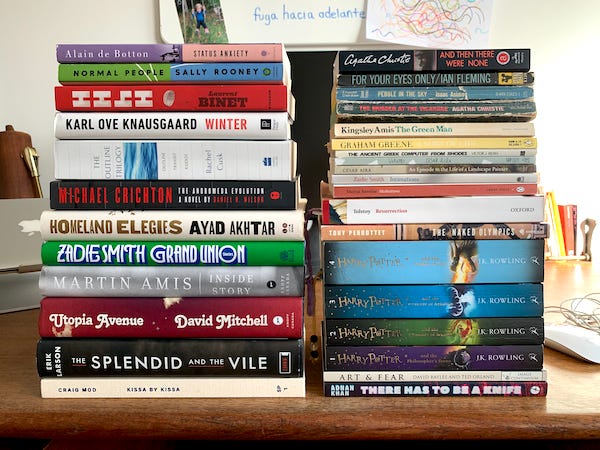

I read thirty books this year, which doesn’t seem like a lot, but also seems miraculous (see above re: this paradoxical year). Ten were nonfiction, twenty were fiction. Every year I make an effort to only read books that were published at least thirty years ago, and every year I fail miserably. 2020 was no exception. Of my five favorite living authors, four of them published new books this year, and even my favorite dead author had a new novel out, so what was I supposed to do?

The 2020 reading list: from Marcus Aurelius to Ayad Akhtar, with a bit of Agatha Christie and a lot of Harry Potter.

/////

One of the activities I missed most this year (yeah, yeah, besides being with family and friends) was going to the movie theatre, and last month I got sucked into watching reaction videos, specifically these supercuts of people in theaters freaking out at the last two Avengers movies.

What film critics often forget when lamenting the ubiquity of these mega-blockbusters is that, for most people, going to these movies is like going to see your favorite band in concert—you’re not there to think critically about the experience, you’re there to hear the hits, the songs you love, and when you hear the first few notes of your favorite tune, you stand up and cheer and start singing along.

For me, there’s no better place to be than a packed-full theater on opening night. And there’s no better moment than when the lights first go down and all the chattering dies down. That hush. Hundreds of people drawing in their breath. The movie might suck, but here, in the first few seconds, when the screen is still black, there exists the potential for it to be great, and everyone in the theatre wants it to be great—that’s why they’re there. That’s what you feel in that quiet moment: hope. Three hundred people hoping hard that they’ll experience something sublime.

That didn’t happen much in 2020. I was lucky to see The invisible Man in theaters right before the world stopped, which was worth it for that one moment, which is best experienced in a theater full of people so that you can witness firsthand the waves of confusion and terror it incites.

Otherwise, it was a discouraging year for the movies: the big tentpole pictures got pushed to 2021 or released on streaming, and I hope we can all agree that the last thing anyone needs is something else to watch on their TVs at home (532 original scripted series were produced in the United States in 2019—more than double the number from just eight years earlier.)

But, as with everything else, it was also an encouraging year for movies: we got the chance to turn back to all the old flicks we’d forgotten about, and this past year, thanks to some excellent programming (and excellent safety measures) at The Mayfair Theater, I was able to see Pulp Fiction, Robocop, and Godzilla vs. King Gidorah on the big screen.

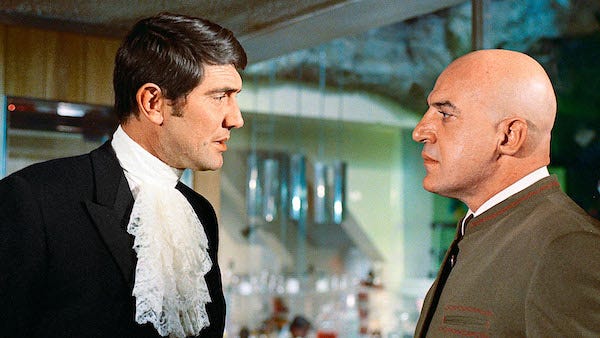

In an effort to give some shape and meaning to my watching habits later in the year, I challenged myself to watch all twenty-four James Bond movies before the end of the calendar year. I managed to get through eighteen, and there were few moments I enjoyed more this winter than the half-hour window between dropping the kids off at school/daycare and the start of the workday, when I’d sit down with a coffee and watch a half-hour portion of an old Bond film. The biggest surprise was On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – the one with George Lazenby, oft forgotten – which was the inspiration for both Austin Powers’ frilly velvet suit and Christopher Nolan’s high-minded epic action sensibility. It’s goofy and intense, absurd and unexpectedly moving—categorically a James Bond movie, yet unlike any before or since. A paradox, like this year.

/////

In 2020, I ran more than any other year; short little jogs, but frequently, consistently.

I listened to more podcasts than music, binging deep into the back catalogues of shows like Blank Check and You’re Wrong About.

The best song of 2020, “Where The F*&K Did April Go?” by The Streets, also had the best lyric of 2020:

We’re all in this together’s the caring headline of the airline

Try telling them that when your bag is three kilos over

When the National Gallery of Canada reopened, I discovered a new path through my favorite wing, and new paintings that had previously eluded me: landscapes by George Morland, James Hayllar’s charming family portrait, and Abraham Solomon’s “First Class: The Meeting…and at First Meeting Loved” which features a young man and woman talking in a train carriage while an older man (her escort) dozes beside them—a work that was met with such hostility by Victorian critics for its vulgarity that Solomon had to paint another version of it in which the older man was awake and sitting between them.

(For young lovers, maybe 1854 was the worst year ever.)

////

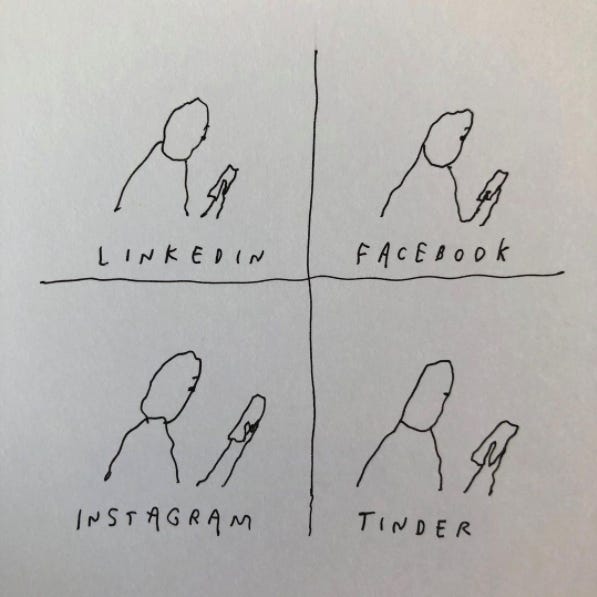

I was sick of the screen in 2020. Sick of scrolling, sick of hot takes, sick of social media; the shallow pageantry of it, the embarrassing pursuit of wealth in the attention economy, the virtue signaling. But I returned to it again and again because I missed other people and wanted to stay in touch, and sometimes reading a friend’s tweet about the movie they just watched, or seeing an Instagram picture from someone’s morning bike ride, was just the thing I needed to remind me that I know other people, and might see them again someday soon.

Yet another paradox of 2020: the source of my discomfort was also a source of comfort.

Drawing by @lianafinck for the New Yorker.

////

This was meant to be our year of leaving home to travel the world. Instead it was the year our home became our world. Our family has endured it better than most, I think, because we are, by nature, solitary creatures: even the school-aged kid didn’t miss school that much—she prefers to be at home, hanging out, doing arts and crafts at the kitchen table, being chased by her brother in the backyard. We’re introverts. We’re homebodies. We secretly love an empty calendar.

In this manner 2020 showed us who we really are by amplifying what was already there. The lonely got lonelier, the anxious more anxious. The productive became hyper-productive, and working parents worked harder at parenting. All the superfluous stuff was stripped away, and what were we left with? Just ourselves. Our true selves. For better or worse.

I’ll go ahead and say it: 2020 was a good year. I know that’s not true for everyone, but it was for me. There were bleak moments, certainly. Unreasonable highs, too. But solitude comes naturally to me, and day-to-day life didn’t change that radically: I was working from home in sweatpants before working from home in sweatpants was a thing. It’s a difficult thing to admit, considering how much others have suffered, but, as Zadie Smith writes in Intimations, her collection of essays from the spring of 2020:

“The single human, in the city apartment, thinks, I have never known such loneliness. The married human, in the country place with partner and children, dreams of isolation within isolation. All the artists with children—who treasured isolation as the most precious thing they owned—find out what it is to live without privacy and without time. The writer learns how not to write. The actor not to act. The painter how never to see her studio and so on. The artists without children are delighted by all the free time, for a time, until time itself begins to take on an accusatory look, a judgmental cast, because the fact is it is hard to fill all this time sufficiently, given the suffering of others.”

Let’s not forget that four short years ago we were all talking about how 2016 was the worst year ever. Trump, Brexit, a plague of mass shootings and terrorist attacks, global temperatures at an all-time high, the Zika virus, the Syrian refugee crisis—a lot of terrible things happened that year. Terrible things will happen in 2021, too—the typical cruelties fate randomly deals out to those who least expect and least deserve them. Good things will happen, too. Good things happened in 2020. We may not remember them, but they did. We found new ways to hang out with friends. We found new ways to feed ourselves. We got to spend more time with our kids, which sometimes felt like a curse, but, looking back, will perhaps be the great blessing of this global pandemic.

If nothing else, 2020 gave us a new perspective. On everything. The interconnectedness of the world. How little nature cares for manufactured concepts like borders and political ideology. How much we rely on other people: for companionship and community, for our mail to be delivered, for our grocery stores to be stocked. How things can be awfully wonderful and wonderfully awful, all at the same time.

2021 begins today.

We’ll see.