Breaking News, Always Broken

Negativity bias, predatory algorithms, the drawbacks of being well-informed.

IN JUST THREE SHORT DECADES, technology has advanced exponentially—every day there seems to be some new tool or process that makes human lives easier, faster, frictionless. The entire world is interconnected. The average person can boast an intimate knowledge of what is happening on the far side of the world. People who were born at the beginning of this era have experienced a radical shift in how they live; they can hardly describe, to their own children, the machines they depended on in their own youth—there have simply been too many leaps between then and now.

Yes, an era of shocking change. The culmination of human achievement. The peak of technological acceleration. The end of history.

I am talking, of course, about the mid-1800s.

Ch-Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes

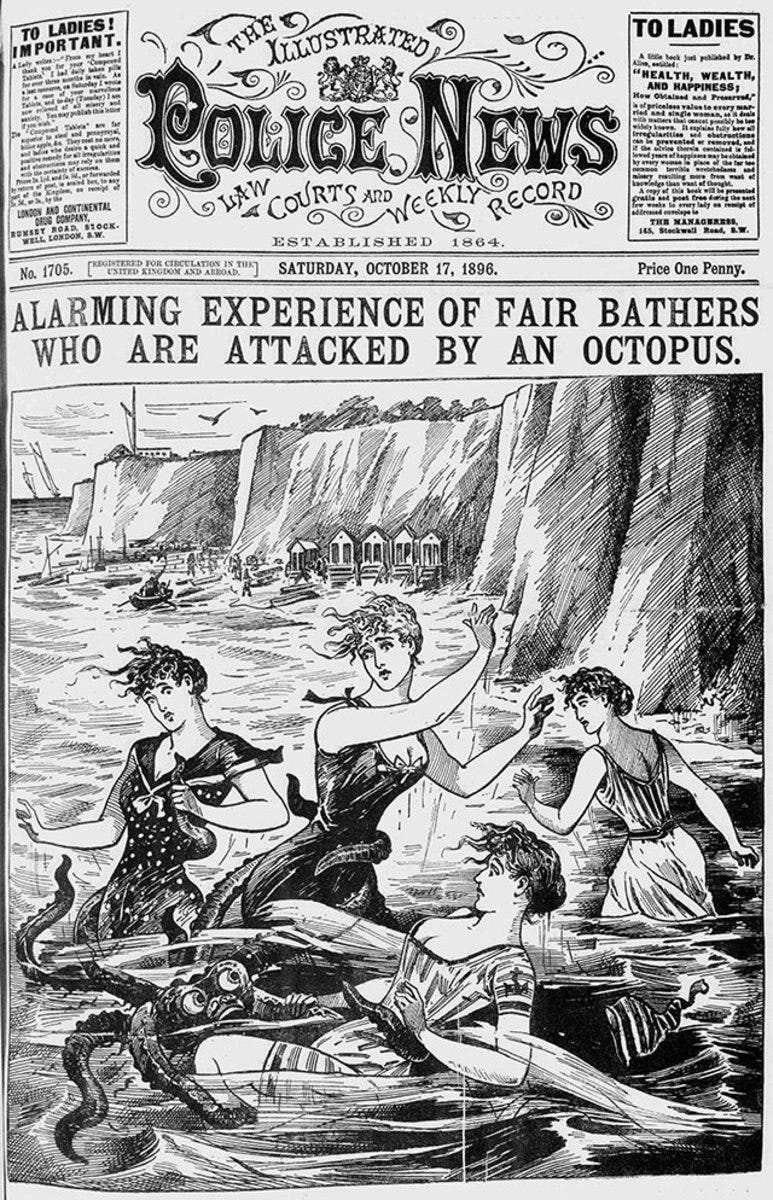

PRIOR TO THE 1850s, the process of making paper relied on expensive textiles like linen and cotton. But at the midway point of the 19th Century, paper manufacturers transitioned to a much cheaper substance: wood fibre. Just a few years after that, the steam-driven rotary press accelerated the speed and efficiency of the printing process. In the decades that followed, the cost of printing a piece of paper fell by ninety-percent.

Steam power was having an impact in other ways, too. With the proliferation of rail lines all over the world, trains were able to move people (and material goods) further and faster than ever before. Information was travelling faster, too. Electric telegraph technology advanced so quickly that by the end of the 1850s, transatlantic cables had shrunk the distance between Europe and the New World to mere minutes.

As all of this was happening, literacy rates everywhere were dramatically increasing. More and more people were learning how to read. And let’s not forget that the middle of the century also saw the development of another essential technology: photography.

So if you were born in, say, 1840, you came into a world where it took several days for news to travel from one city to another, where you likely had no idea what was going on elsewhere in your own country, let alone another continent; a world where a daily newspaper was an expensive indulgence of the rich and influential. By the time 1883 rolled around, and you turned forty-three (the age I am today), you could open a morning newspaper that had been printed in a city hundreds of miles away, that cost only a few cents, and whose headlines – and maybe even a picture! – would tell you, in sensational detail, what was happened on the other side of the planet. Nothing now stood between you and the news.

And the news was probably bad.

Train derailments. Corrupt politicians. Missing children. Killers on the loose. If the broadsheets of the late-1800s were lucky, a child would be killed in a train derailment after being kidnapped by a murderous city councillor. Because right from the very start, newspapers knew exactly how to make readers pay attention.

Bad News Was Good For Evolution

NEGATIVITY BIAS IS A PHENOMENON in which negative stimuli, experiences, or information are perceived and remembered with greater intensity than positive ones. We are attracted to bad news. We pay closer attention to it. We absorb it faster. We internalize it.

But what might seem like an evolutionary flaw is actually an evolutionary feature. Over the two million years that homo sapiens spent as hunting-gathering nomads, individuals who were more highly-tuned to threats — predators, poisonous plants, aggressive neighbours — were more likely to survive and pass on their genes. Their ability to quickly recognize and respond to negative stimuli provided a selective advantage.

This makes sense, of course. When it comes to life-or-death choices, you can only make a mistake once: we are all descendant from the lineage of the guy who stayed awake all night watching out for sabre-toothed tigers and not the guy who figured the noise in the grass was probably just crickets and went to sleep. Even minor negative events tend to have more immediate and significant consequences than positive ones. Falling and breaking your arm is certainly more memorable than all those times you didn’t fall and didn’t break your arm. All the oysters you’ve eaten than haven’t gone bad certainly pale, in your memory, to the one that did.

It makes perfect sense for organisms to prioritize negative information and to encode it more deeply into memory to avoid future harm.

At least it did.

Breaking News is Designed to Break You

NEGATIVE HEADLINES in news and social media posts receive more engagement than positive ones. This, of course, is a result of negativity bias: our defensive mechanism is triggered, we’re trying to protect ourselves. News organizations know this—and they prey on it. Their revenue is directly generated by your attention (the more you click, the more money they make) and what better way to lure you in than with the exact kind of news you are genetically incapable of resisting?

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when what we needed most was reliable information about what was happening in our radically altered world, what we got instead were incessant updates about rising death tolls, overwhelmed hospitals, and the negative economic impacts (both real and imagined) of people not being able to eat at restaurants. These stories dominated the news cycle because they got clicks. They got clicks because we were afraid. Meanwhile, all the stories about the heroic efforts of healthcare workers and the miraculous development of a vaccine were pushed further and further down the page.

The development of the COVID-19 vaccine should go down in history as one of the modern era’s most remarkable feats of scientific collaboration. Typically, vaccines take years, if not decades, to develop. In the early days of the pandemic, the most optimistic forecasts predicted that a COVID-19 vaccine would take, at minimum, two years to produce (many believed it would be closer to five). What happened instead? The first vaccines were approved only 11 months after the start of clinical trials. We stayed in lockdown half as long as we might have. Maybe less. A testament to what can be achieved when the global scientific community collaborates and mobilizes its resources to tackle a common challenge!

And what did our news providers feed us instead?

Stories about rare adverse reactions. Stories that amplified rumours and half-truths about its effectiveness. Stories about the logistical challenges of the rollout, delayed shipments, how hard it was to book an appointment. We were witnessing a modern miracle, but the news told us we were being scammed. It made us suspicious and cynical, because, for the news, suspicion and cynicism is good business.

We’re In It Together

YOU MAY BE THINKING, yes, this is totally true of those other news sources—those right-wing/left-wing papers, those fake news/mainstream media sites, those liars and profiteers on the other side of the political spectrum. But the failure of our news institutions is universal. From the CBC to Rebel News, from the New York Times to Fox News, from the Huffington Post to the National Post and everywhere in between—they’re all guilty of these crimes.

The problem isn’t the news that other people are getting.

The problem is way the news itself has evolved.

Feeding The Pigs

THE WORST FEATURE OF THE NEWS, today, is the fact that we can’t get away from it. Owning a device — any kind of device — is akin to having an Uber Eats driver perpetually dropping off Big Macs at your doorstep. We are forced to live in a constant state of resistance. And resistance isn’t easy.

All the tools we use to connect with friends and family have built-in functionality — alerts, notifications, pernicious algorithms — that are designed to put bad news (the news we’re genetically predisposed to internalize) in front of our faces every single minute of every single day. We no longer seek out news, it's fed to us. The same way pigs are fed through automated troughs, receiving pellets of processed food without any regard for their individual needs or natural rhythms.

We can’t look away. Looking away — like the dead branches of our family tree who fell asleep while the sabre-tooth tiger was stalking them — might put us in danger. Everything, then, feels urgent and alarming. We are perpetually anxious about what is happening in our city, in our country, in other cities, in other countries—on other planets, even. And this anxiety compels us to keep checking our phones. There must be more to know, more to be worried about! And there always is. The more anxious we are, the more we check. The more we check, the more we find to be anxious about. We’re stuck in a negative feedback loop that we can’t escape from. And all we wanted to do was answer that text from our mom.

One can’t help but feel powerless when force-fed all this negativity. So much is wrong with the world, and, the hard truth is, there’s not much we can do about most of it. We are left feeling powerless, and there are two common responses to a feeling of powerlessness. Apathy and rage.

The modern news forces us to live between these two poles.

North vs. South

IT’S EVEN WORSE if you’re Canadian.

We face a unique problem in the Great White North: we live right beside the biggest, most powerful, most highly-weaponized mass-media consortium on the planet. American news is our news. We can’t get away from it. A 2017 survey found that 56% of Canadians watched American news regularly, while only 36% watched Canadian news regularly. And we don’t merely prefer our news to come from American sources—we want it to be about America, too. According to a 2017 study, only 23% of the news stories consumed by Canadians were actually about Canada, while stories about the U.S. accounted for 68%.

And why wouldn’t we? It’s so well-produced. It’s so entertaining. The United States does everything bigger and better, and the way they create and disseminate news is no different. Gigantic portions, horrifying combinations, questionable ingredients—is it all that surprising that the country that invented the KFC Double Down found a way to turn information into fast food?

The Drawbacks of Being Well-Informed

IT’S EASIER THAN EVER to feel like we “know what’s going on”—but do we?

Does closely following the news — scrolling Twitter and Facebook, watching CNN, clicking on every notification to find out about every bad thing that is concurrently happening on our planet — really make you knowledgeable?

In his 1984 novel, "The Unbearable Lightness of Being” — which is set in Communist Czechoslovakia during the Prague Spring of 1968 — Milan Kundera describes a type of person who consumes the news voraciously but cannot (or simply refuses to) make the effort to fully understand what they read. They are:

“…well-informed about everything, like a needle that has been stuck into all the newspapers, but incapable of understanding anything, like someone who has been deaf and blind from birth.”

Kundera coined a term for these people: Well-Informed Idiots.

Is Blissful Ignorance The Alternative?

THERE’S A NEGATIVE SOCIAL STIGMA attached to people who don't closely follow the news. Being “informed” is often seen as a civic duty or responsibility. We are told that “when we have the privilege to not be directly involved in conflict, social issues, or climate change, we have the responsibility to show up and care.”

But do we? This expectation — that we must care deeply about the awful things happening on the other side of the world — is precisely the psychological vulnerability news organizations and social media algorithms exploit to make us pay obsessive attention to their product (and it is a product, no different than an iPhone or can of Coke).

Being aware of current events, we are told, is crucial for participating in democratic processes and being an informed citizen. This is true. Except that we have confused the concept of “being informed” with “taking action”—knowing about something is not equivalent to doing something about it. And the truth is, there’s often little we can do about the news stories the algorithm feeds us.

We have no responsibility to care about the news happening in other countries, or even other cities—we have no responsibility to care about anything. This pressure to care is precisely what pushes people away, turns able collaborators into false allies, convinces people that changing their profile pictures to support the cause of the day is a meaningful contribution, that “raising awareness” is a tolerable alternative to the difficult work of making change.

While we watch the far horizon, waiting for an update about what’s happening beyond our reach, what are we missing in the foreground?

A few weeks ago—

—a 74-year-old grandfather was hit by a car and killed while walking his dog on a busy road just a few kilometres from where I live—the same busy road I sometime go jogging on.

Why do I know more about George Santos than I do about this man? Why do I know more about gun violence in Mississippi than I do about the violence happening on the roads I’m running on?

Ch-Ch-Ch-Ch-Changes: Part II

LET’S GO BACK TO THE LATE-1800s. The media landscape — particularly in the United States — is highly sensationalist, highly negative. The newspaper industry is dominated by a handful of powerful publishers who compete fiercely for readership. Articles are designed to provoke strong emotions in readers: crime, corruption, scandal, tragedy. Stories are based on rumour, speculation, and opinion. Depending on which newspaper they read, people can make up their own facts.

(Does this sound familiar?)

So, what happened? The news didn’t stay like this. If it had, the regression we’ve experienced in the last decade wouldn’t seem so jarring. The early part of the 20th Century is considered to be the Golden Age of Journalism. During that time, the news media — which, let’s admit, has never been perfect — nonetheless began to live up to its potential as a tool for social engagement, a way to empower people with information. What changed?

We changed.

Us, the people who receive the news. We became more educated, more literate, and as the general population became better readers they demanded better coverage. They turned to alternate sources — radio and television — and consumed a more diverse diet of information. They became more progressive, more interested in social and political reform, and this led to a greater demand for more informative stories about more important issues. In response to these changing preferences, newspapers began placing a greater emphasis on accuracy and substance in their news coverage. Journalists began to embrace the importance of objective reporting, separating fact from opinion and striving for impartiality in their coverage. Context was established between local, national, and global news, and a chain of trust was built between the general public and the institutions that provided them with information.

The news didn’t change. We forced it to change.

What does change look like in 2024?

I’M AS GUILTY AS ANYONE of being seduced by the easy pleasures of the modern news. I’m only human. Sometimes – even while a land war is raging in Europe, even while local zoning laws are being hotly debated – what I really need to know is whether or not Harry Styles spit on Chris Pine.

But just like when you’re practicing meditation, the point isn’t to achieve perfect focus, only to recognize when your focus is slipping. Here is some advice that I try (and often fail) to live by. Perhaps you can fail to live by it, too.

Disengage from your screen.

Rutger Bregman offers this advice in his book Humankind (yeah, I’m talking about it again).

One of the biggest sources of distance these days is the news. Watching the evening news may leave you feeling more attuned to reality, but the truth is it skews your view of the world. The news tends to generalize people into groups like politicians, elites, racists and refugees. Worse, the news zooms in on the bad apples. The same is true of social media. What starts as a couple of bullies spewing hate speech at a distance gets pushed by algorithms to the top of our Facebook and Twitter feeds. It's by tapping into our negativity bias that these digital platforms make their money, turning higher profits the worse people behave. Because bad behaviour grabs our attention, it's what generates the most clicks, and where we click the advertising dollars follow. This has turned social media into systems that amplify our worst qualities.

Neurologists point out that our appetite for news and push notifications manifests all the symptoms of addiction, and Silicon Valley figured this out long ago. Managers at companies like Facebook and Google strictly limit the time their children spend on the internet and 'social' media. Even as education gurus sing the praises of iPads in schools and digital skills, the tech elites, like drug lords, shield their own kids from their toxic enterprise.

My rule of thumb? I have several: steer clear of television news and push notifications and instead read a more nuanced Sunday paper and in-depth feature writing, whether online or off. Disengage from your screen and meet real people in the flesh. Think as carefully about what information you feed your mind as you do about the food you feed your body.

Seek news, don’t let it come to you.

Turn off your alerts and notification. Don’t rely on social media algorithms to tell you what’s important. Buy a physical newspaper and read it from front to back—learn new things by accident.

A much smarter and more enlightened friend of mine recently explained:

Not all news is created equal. There is excellent long-form journalism that contextualizes, and expands horizons, and explains the human experience. There is excellent “news” that informs, enlightens, explains, humanizes. And then there is news that does the opposite. And, personally, I’m finding it easier and easier to access the latter and easier to ignore the former.

Follow local news.

Know what’s happening within a few kilometres of your house—these events, while not as dramatic, are likely to affect you much more directly than what’s happening, say, in the British Parliament (as hilarious as those events often are).

Ignore headlines.

You don’t know the story from the headline because headlines are purpose-built to be misleading. They are meant to make you think the story being summarized is more frightening, urgent, relevant, or unique than it really is. But it’s not. They just want you to click. So, when you do, read to the bottom of the page to get the full context, and decide for yourself whether it matters.

Listen to more podcasts, subscribe to more newsletters (wink).

In the same way that the advent of television and radio diversified the media landscape in the middle of the 20th Century, there are more and more ways to get news and information, and the best of these are created not to take advantage of your negativity bias, not to provoke a lizard-brain reaction, but to enable a deeper and more nuanced understanding of an issue. These alternate sources are themselves biased and prone to hyperbole (case in point: the title of this essay), but they can provide and alternate angle, and the more angles you have on a particular thing, the better you can see its shape.

What The News is For

KNOWLEDGE IS SUPPOSED TO EMPOWER US. Reading the news should make us feel deeply engaged with the world. It’s supposed to help us connect with others—particularly the people who live differently than we do. It should help us understand them a little bit better. It should make us compassionate.

After navigating your way through all your feeds and notifications and alerts and all the articles that have been shared by friends and flashed in your face by social media algorithms, do you feel engaged and empowered? Do you understand the other viewpoint a little bit better? Do you feel compassionate?

Or does it make you feel helpless and afraid?

When you read the news, do you see all the ways you can live a better life—or are you seeing enemies hidden in the tall grass?

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this particular issue of TOLSTOYAN, you can share it with a friend by clicking the button below.

I’d love to hear about how you get your news. You can get in touch by responding directly to this email, or by clicking the button below to leave a comment.