Plague Journal, Vol. 3

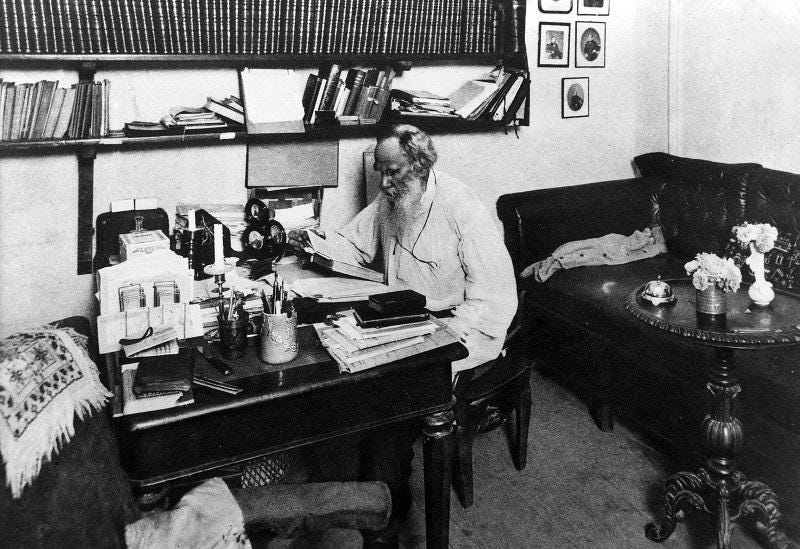

Photo: Leo Tolstoy, in 1908, looking pretty much exactly like I look in 2020.

“A feeling of inability to advance in art, a sense of his incapacity, came over him. Seven years before this he had given up military service, feeling sure that he had a talent for art, and from the height of his artistic standpoint had looked down with some disdain at all other activity. And now it turned out that he had no right to do so, and therefore everything that reminded him of all this was unpleasant.”

This is a passage from Leo Tolstoy’s Resurrection, a book that holds a unique place in my family’s history; the royalties he earned from it paid my ancestors’ way across the ocean. It holds a unique place in my psyche, too, as it describes with eerie precision my current mood.

No work updates. It’s all still happening. But often isn’t. Everything that reminds me of it is unpleasant.

////

I’ve deleted all the news apps off my phone, turned off all notifications, hidden my web browser on a separate screen, made all my habitual headline-checking as difficult as possible. Blissful ignorance, self-imposed. But I’m not entirely oblivious to what’s happening in the world right now; it turns out that the news that matters will find its way to you through that supposedly obsolescent channel: word of mouth. Chatting across the fence with neighbours, by text with friends, by phone with parents—I’ve found this to be a great way to filter out rumour and augury, to evade all those headlines and snippets purpose-built to make you anxious and afraid and click, click, click. The value of a smartphone is to be connected, and yet, to be connected, you don’t need a smartphone, just a capacity to listen. Another lesson to learn in the midst of The Great Isolation.

////

Isolation, seclusion, segregation, retreat, withdrawal—there are a lot of words that describe the state of being alone. I prefer the term solitude.

Solitude is a different kind of aloneness. It’s autonomous, virtuous—and, for people like me (introverts, loners, egoists, narcissists) a necessary form of sustenance. April and May were supposed to be my months of solitude. My whole year was aimed towards them. My wife and I had planned a two-week trip to Greece, just the two of us, alone, our first vacation without the kids. Our itinerary maximized the time we’d spend in small villages on small islands, including a stretch at an isolated house in the middle of an olive orchard in the hills of Crete, far away from everyone and everything. After we returned from that trip, I was meant to be in Argentina for a month or so, holed up, all alone, in a small office in La Plata, where I was going to write the next next book.

I purchased these periods of solitude with money. I invested time and effort to acquire them. They were on purpose. A sort of spiritual quarantine, isolated from the responsibilities of regular day-to-day life and the cumulative pressure they exert. I machinated for years to acquire this aloneness.

And now?—the world is suffering an abundance of aloneness, and, ironically, I’ve never possessed less of it.

Not to say that quarantine is a torment. It’s not. There’s much joy in our house. How can there not be, with two kids who have inherited my interiority, who prefer to quietly draw pictures and build couch-cushion forts and contemplate piles of loose Lego. They love being at home, and we love it, too. But you can love a thing and be depleted by it, and, despite how well we’ve adapted, despite how much we’ll miss it when it’s over, these have been some of the most depleting weeks of our lives.

Henry Miller said it well.

“I need to be alone. I need to ponder my shame and my despair in seclusion; I need the sunshine and the paving stones of the streets without companions, without conversation, face to face with myself, with only the music of my heart for company.”

/////

But it turns out that solitude, to a certain degree, can be self-generated, and with the psychic space I’ve freed up by cutting myself loose from the daily compulsion of “checking the news” I’ve been able to spend a bit more time in the past trying to make sense of the present.

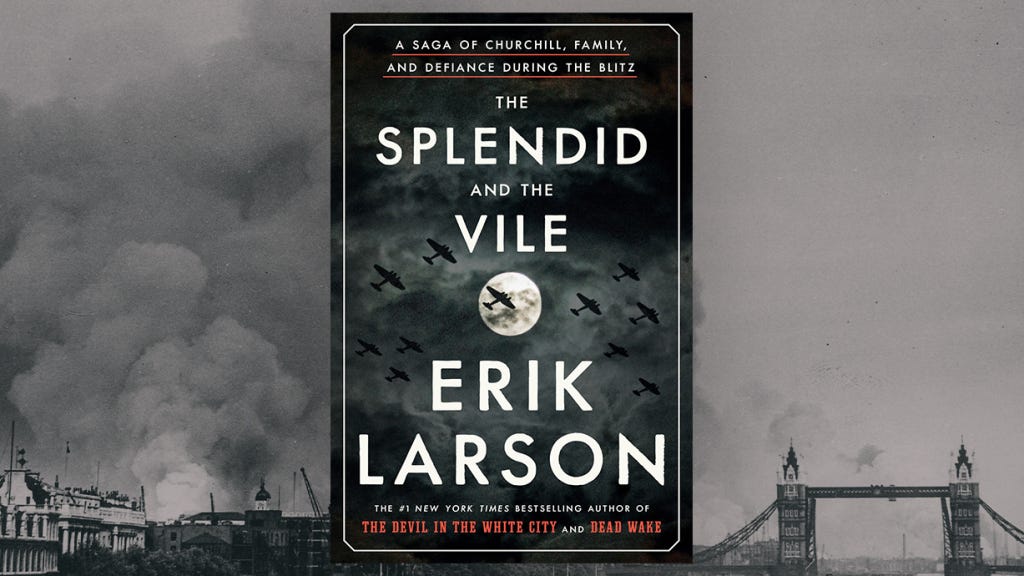

I just finished Erik Larson’s The Splendid & The Vile, which documents Winston Churchill’s first year in office and the concurrent German bombing campaign against the UK, and which I enjoyed so much that I had to ration pages to keep myself from finishing too quickly.

As with everything I read or watch, lately, it all seems terribly relevant to the strange consequences we’re right now living through. From the unfolding of day-to-day life in the midst of extraordinary circumstances—

Scores of residents did die, and the onset of night became a source of dread, but day by day, life took on a strange normalcy. The shops of Picadilly and Oxford Street still teemed with customers, and Hyde Park still filled with subathers, more or less confident that German bombers would not pass overhead until dusk.

To the empty shelves one encounters on trips to the grocery store—

Rationing remained an irritant, especially the total absence of eggs in stores, but here too one could adapt. Families raised hens in their yards…a Gallup poll found that 33-percent of the public had begun growing their own food or raising livestock.

To the proliferation of disinformation—

Rumours flourished. Air raids and the threat of invasion left fertile ground for the propagation of false tales. To combat them, the Ministry of Information operated an Anti-Lies Bureau, for countering German propaganda…anyone spreading false stories could be fined or, in egregious cases, imprisoned.

One thinks back on this period as one of great moral courage—an entire country united in stoic defiance. And indeed this was true: the bombing campaign was designed to intimidate, weaken resolve, compel the population to ditch their current government and elect one that would seek a peace agreement. But the British people refused to be cowed, and, over time, the Nazi leadership was utterly confounded by their perseverance; even Goebbels, at one point, wrote admiringly in his journal of how stiffly they withstood it all.

And still, during this time, as one of history’s great leaders was exercising one of history’s great feats of leadership, there were those who thought Churchill’s policies were reckless, who believed the best path was to seek peace with Germany, and they actively fought – both politically and in the press – to undermine him. Knowing what we know now, it’s impossible to fathom the logic of this argument. But that’s the thing: we never know what we will eventually know, and can only hold faith that:

“The arc of the moral universe Is long, but it bends toward justice.”

////

That, of course, is one of Martin Luther King’s most famous quotes. But it didn’t originate with him. He paraphrased (and improved) this thought from an 1853 sermon by abolitionist minister Theodore Parker. The original statement was:

“I do not pretend to understand the moral universe. The arc is a long one. My eye reaches but little ways. I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by experience of sight. I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends toward justice.”

There is a parallel thought to this that I think might explain my compulsion to step back from the news cycle—something along the lines of: the arc of history is long, and it bends towards reason and rationality. Why drown yourself, then, treading water in the present moment’s bad prognostication?

/////

No accident that I’m quoting Martin Luther King right now. The death of George Floyd and others might make you question King’s faith in the moral universe’s trajectory, but there may be no better time than now, with the systems and structures that constrain us in such fragile shape, for the tinderbox to be lit. There have been protests like this before, but they have rarely been so timely. One hopes they can catalyze some sort of tangible change: in policy, in leadership.

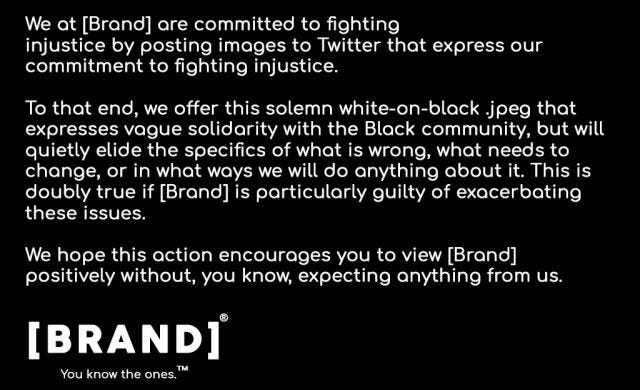

And one asks, of course: what can I do? I feel cynical about the shortcuts we take to fake engagement with complex, painful problems like racism. To me, gestures of support on social media – liking, sharing, changing your profile picture – are no different than those turn-of-the-century exercise machines with vibrating belts that supposedly build your muscles while you stand immobile. Change requires hard work, and hard work hurts. In my estimation, unless you’re doing something hard, something that

hurts, you’re not changing anything.

To that end, if you want to do a bit of hurtful self-examination, you can take Harvard University’s Implicit Skin-Tone Bias Test. It only takes ten minutes or so, and partway through you’ll probably figure out how it works. But by then, it will be too late. My results: a moderate preference for light-skinned people, which is Harvard’s polite way of saying the I have a moderate disfavor towards dark-skinned people.

Knowing this about myself, what right do I have to feed my ego by sharing woke hashtags from the safety of my suburban home?

For anyone who proudly proclaims that they don’t see skin colour, you can suggest that they read about individuation and learn how self-deceiving the idea of “colourblindness” really is.

The big problem is that “colorblindness” keeps us from actually seeing each other. By working overtime to deny what is immediately in front of our faces, we stop seeing people as individuals. When we stop seeing people as individuals, we are more likely to have our actions governed by unconscious stereotypes, and biases.

So: what can I do? I’m not keen on protesting—I don’t have the heart for it (but greatly admire those who do). Instead, I’m going to do what I do best: start with myself, and try to understand the invisible ways I contribute to the problem.

/////

And when you’re done with that test, you can cheer yourself up by taking this one (how’s that for an awkward transition?): watch these incredible videos from Dear Cast & Crew, which showcase the best movies from A to Z in every cinematic genre, and see how many you can guess before the titles appear onscreen. It’s surprisingly fun, especially when you recognize your favorites, and the skill and precision with which they’ve been cut together by Casey Tourangeau is just masterful (the transition from R to S in the Action Movies video is particularly brilliant).

The greatest movies of all time: A-Z | Dear Cast & Crew

None

/////

I’m still running. But in the mornings, now. Fewer rabbits more coyotes. Summer has diluted those postapocalyptic vibes—or maybe the postapocalytpic vibes have become the new normal. Who knows. I certainly don’t. And neither does anyone else. I take solace in the fact that, across race and gender and class, we’re all equally ignorant about what the future holds. A week from now, a year from now—no one can see it. Blindness: the great equalizer.

I guess we should enjoy it while it lasts.