Plague Journal, Vol. 2

Photo: Milan Kundera, the exiled Czech writer, who celebrated his 91st birthday just a couple days ago, giving the same what-the-fuck-do-you-want? look every writer gives to the person who interrupts them at their desk.

Strange times continue.

Nightly runs through the neighbourhood are proving to be a good and necessary form of decompression at the end of the day—like a deep sea diver returning to the surface world, you have to find a way to keep your blood from turning toxic after spending so much time under these unnatural pressures. On my run the other night, I saw two rabbits sitting just a few meters away from one another (territoriality: the original social distancing). One of them was dead center in the middle of the road, on the dividing line, ears up, checking things out. No traffic on these streets anymore, so why not hang out in the middle of these formerly perilous places? I’ve been running along the dividing line, too. Headphones on, oblivious to danger. So far, no approaching headlights have forced me onto the sidewalk.

I like walking in the middle of the road. In Yellowknife, we used to live on Basillie Court, which was, back then, the very outskirts of town; the rocks behind our house stretched all the way to Kam Lake Road, and, beyond that, the industrial park. Past that, nothing. I had a friend over for a sleepover, once — he lived somewhere “downtown” — and that night (or maybe early evening, who can tell with the northern sun’s erratic seasonal schedule), as we walked back from wherever we’d been, I remarked, with much self-satisfaction, about how pleasant it was to live in such a remote neighbourhood, so quiet that you could walk in the middle of the road without a care. In all the years since, I’ve imagined that the silence that followed was a moment of deep reflection to my friend, but I now realize that he was probably politely ignoring my patronizing.

/////

I’ve been thinking a lot about how well-suited I am to this state of isolation, which means I’ve been thinking a lot lately about growing up in Yellowknife, and how, perhaps, it conditioned me to bear what are, for some, this unbearable state of affairs. Limited groceries, limited supplies, limited transit, limited access to the services and luxuries that people in even the remotest rural places down south could at least drive themselves to—the first half of my life was defined by these circumstances. Before the McDonald’s was built, people travelling south would buy Big Macs by the dozen, fly them home, distribute them to friends. A March Break trip to West Edmonton Mall was a chance to stock up on the essentials of teenage life: Hypercolor shirts, Starter caps, whatever CDs and VHS tapes you couldn’t find at Top Forty, the local record store. In spring and fall, when the ice road across the Mackenzie River was breaking or freezing up — and therefore impassable — supermarket shelves were barren. You drank powdered milk, and when fresh milk arrived (if you were quick enough to get some) you paid double the price. Fresh fruits and vegetables? Yeah, no. Good luck with your gluten-free vegan diet. Much of this was invisible to me, as so many things in childhood are, but, still, there’s something about our current lifestyle — homebound, making do with what’s available, not missing what isn’t — that feels perfectly comfortable to me.

I was imagining, the other day, what it might feel like to live in Yellowknife right now, isolated from all the isolation; how self-satisfied I’d probably feel to have chosen a life in the middle of all that empty space—especially now that empty space has become such a precious commodity. But I was chatting with my friend Amy, who I’ve known since the first grade, and who still lives in Yellowknife, and she explained to me how the geographic expanse of the Northwest Territories actually puts them in a very precarious place:

“It’s hard to get information to people in small communities who have shit internet access and can’t speak/read English. They are desperate to prevent COVID from getting into the smaller communities as they don’t have anywhere near the medical support in place to deal with even five really sick people. So far so good. Everyone is home, for the most part. All government employees have been sent to work from home. Lots of private sector people are out of work, like everywhere else. People are working really, really hard to keep things functioning, but it’s not sustainable, they’re going to start burning out, and with our itty-bitty population I’m not sure how we will deal with that. But: one case. Every day I think that this will be the day that jumps…but it hasn’t yet.”

And then she adds:

“It’s still winter, too. And cold. Which sucks. I haven’t left my house since Friday.”

I’ve been wallowing in the tropics of central Ontario for so long that I’ve forgotten what a real winter is like. As I write this sentence, it’s minus-28 in Yellowknife.

/////

I’ve been thinking a lot about Yellowknife for other reasons, too. It’s the subject of my next book, which I am intermittently, methodically continuing to write. At the moment, it’s about 10-percent complete. Or maybe 90-percent. Who knows. It will either be a slim little volume or a thousand-page doorstop. It all depends on when I finally give up. As they say: nothing is ever finished, only abandoned. I had planned, this spring/summer, to cast aside a few other responsibilities and delve deeper into speculative stuff, but global pandemics change plans and perspectives alike, and right now I can see that my paid work, which has (so far) carried on as usual, is a privilege and not an obstacle.

/////

Another good and necessary form of decompression, lately, has been escaping into the past. I am finding some consolation in contemplating the sheer vastness of Time and all the things that have happened, ever. All the trillions of people who have preceded us believed themselves to be a alive at the essential moment of history, and, of course, they were—but that essential moment is perpetually replaced by a new one, and what we experience in the present very quickly becomes inessential. History doesn’t end. There’s on such thing as “this is how it’s going to be from now on” because “from now on” is an inconstant variable. Times change, belief systems are replaced, new cultural norms and political structures are established, and the only thing, really, that remains constant throughout it all is human behaviour. Which is sometimes awful, sometimes noble, and pretty much always hilarious. That, I think, is what brings me solace. The knowledge that no matter what age you live in, no matter the social or technological circumstances, we are inevitably, unflinchingly, unfortunately ourselves.

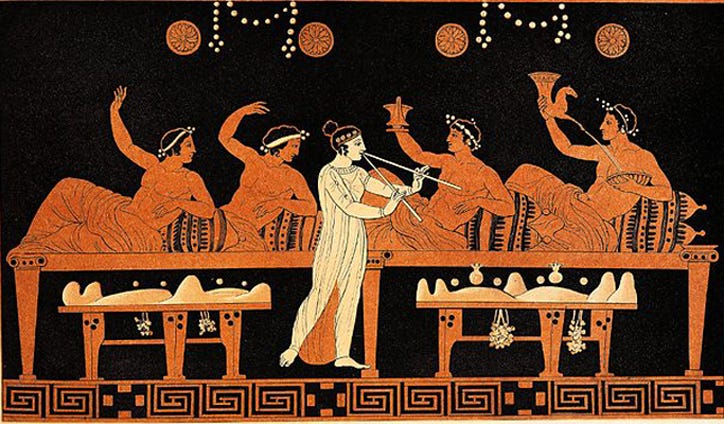

Think about fad diets. They seem like a uniquely contemporary invention, don’t they? Atkins, Paleo, Veganism, these shortcuts to good health, all of them based on some exciting new revelation in biological science, or some nostalgic glance backwards to simpler times when we were gathering berries and barbecuing mammoth steaks and living what we believe to have been purer, more legitimate lives.

But dieting—and the promotion of fad diets by those seeking to profit from them—has been a thing since humans started eating for pleasure. And we dieted back then for the same reasons we do today: to look good; to be thin, lean, muscular; to achieve the ideal physical form dictated by contemporary fashion. Here’s Tony Perrottet, on the eating habits of Ancient Greeks:

“Fad diets proliferated. Learned dieticians would debate which fish were healthier, those from swamps or deep-sea fish? Were fish that ate seaweed better for you? Or fish that ate algae? Some advocated pork—provided the pigs had been fed on cornel berries or acorns. Swine raised by the seas were injurious to health; those brought up near rivers were even worse because they may have fed on crabs…Ideas for extreme diets came from all quarters. Charmis of Sparta, an Olympic sprinting champion in 688 BC, espoused eating nothing but dried figs. Xenophon advised athletes to avoid all bread, the first nonyeast diet in history. The Pythagoreans forbade their athletes to touch beans—but Galen recommended a high-bean diet for gladiators, provided the beans were properly boiled to avoid flatulence. Hippocrates considered cheese to be a “wicked food,” despite the fact that it was supposedly the staple of superhuman Homeric heroes. In the end, much like today’s diet fads, Greek dietary recommendations were so contradictory as to be meaningless.”

Think of the internet, too, and how much we blame it for changing our behaviour—how it has turned us all into shameless self-promoters, ruined rational discourse, weaponized misinformation. But read Dio’s observation about the panegyreis (“profane festival”) which preceded the ancient Olympics, circa 100 A.D.:

“It was an excellent place to be if you wanted to hear crowds of wretched philosophers heaping abuses on one another—an endless number of historians reading their imbecilic writings—innumerable poets reciting their drivel to the wild applause of other poets—gaggles of magicians showing their tricks—throngs of fortune-tellers selling fortunes—countless lawyers perverting justice—or armies of peddlers hawking whatever rubbish came to hand…”

Sound familiar? If not, you probably haven’t been on Twitter or Facebook lately.

Side note: the philosopher Dio was known as “The Golden-Tongued” which makes him sound like one of the founding members of Wu-Tang Clan, and makes the above passage sound like one of history’s earliest diss tracks. Dio is also famous for penning the following proverb in 94 A.D.:

“Ready to give up so I seek the old earth, who explained working hard may help you maintain, to learn to overcome the heartaches and pain.”

Just kidding. That was Inspectah Deck on “C.R.E.A.M.” in 1994 A.D.

Times change, great philosophies don’t.

/////

More history stuff:

The excellent Tides of History podcast has reposted a few old episodes about historical plagues: one about the Justinian Plague, which, concurrent with a major climate shift (sound familiar?) is thought to have accelerated the end of the Roman Empire, and one about The Black Death, which, for quantitative context, killed 60-percent of Europe’s entire population (around 50 million people) between 1346 and 1353. I’m also a big fan of Dan Carlin, whose Hardcore History podcast is the most compelling university lecture you don’t have to go into crippling debt to enjoy. In the latest episode of Common Sense, his other podcast, he offers some optimistic thoughts on where we might go from here:

“If you do look at your history books, it’s funny how often periods like what we’re going through now often end up with reform periods coming afterwards, like they’re a slap in the face that highlights a problem we should have noticed before, and after that situation passes, efforts are made to remedy it…”

/////

There are a lot of interesting pieces, right now, about plagues and pandemics in literature, and one of the best comes from my friend Josh Greenberg, Director of Carleton University’s School of Journalism and Communication, who writes about Albert Camus’ The Plague and what it tells us about the role of media and social memory in times of crisis. Two of Josh’s (many) specialties are health and crisis communications, so, as you can imagine, he’s pretty busy at the moment, and worth a follow on Twitter if you’re into sober media criticism, classic vinyl, or expensive whiskey.

There was another good piece in the New Yorker, which offered a broader history of the literature of pestilence. It touches on Camus, too, along with some other works, among them a story by Mary Shelley called “The Last Man” that sounds like it would make a pretty cool Netflix series.

/////

Around this time last year I was reading Milan Kundera’s Art of the Novel, which turned out to be a lot more insightful about the human condition than it was about plot structure or how to get an agent to read your manuscript. The passage below has stayed with me since then; I think about it often. Kundera is speaking in the context of finding a novel’s central dilemma, which is, he argues, a character asking themselves: why am I here? But he goes on to explain how that question has become complicated in the modern age.

“That life is a trap we have always known: we are born without having asked to be, locked in a body we never chose, and destined to die. On the other hand, the wideness of the world used to provide a constant possibility of escape. A soldier could desert from the army and start another life in a neighbouring country. Suddenly, in our century, the world is closing around us. The decisive event in that transformation of the world into a trap was surely the 1914 war, called (and for the first time in history) a world war. Wrongly “world.” It involved only Europe, and not all of Europe at that. But the adjective “world” expresses all the more eloquently the sense of horror before the fact that, henceforward, nothing that occurs on the planet will be merely a local matter, that all catastrophes concern the entire world, and that consequently we are more and more determined by external conditions, by situations that no one can escape and that more and more make us resemble one another.”

I’ve always thought the heart of this passage is the part about how we “more and more resemble one another,” but, boy, that part about all catastrophes now concerning the whole world is disturbingly literal at the moment.

/////

The other night, during my run, the sky was clear and the stars were bright, and I immediately wondered if this grand cosmic display had been catalyzed somehow by everything that’s happening around the world. Fewer cars on the road? Fewer planes in the sky? Fewer lights polluting the darkness? But it occurred to me that the night sky has always been there, cloudless evenings aren’t rare, and the thing that has changed isn’t the atmosphere—it’s me. I’m noticing things that have always been there.

/////

A quick postscript to say, I always love hearing back from everyone, so feel free to respond with whatever thought, feelings, ideas, counterarguments, or criticisms might occur to you. And if you know someone who might occasionally enjoy reading frightening quotes from Milan Kundera and being trolled with Wu-Tang lyrics, feel free to pass this link/newsletter along.

Enjoy your decompression. Walk in the middle of the road while you still can.