Plague Journal, Vol. 1

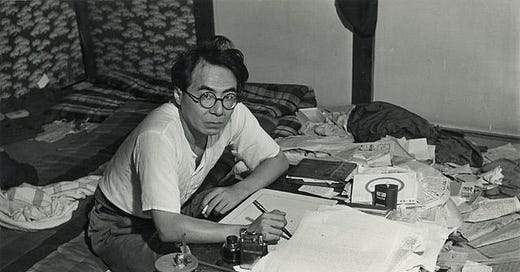

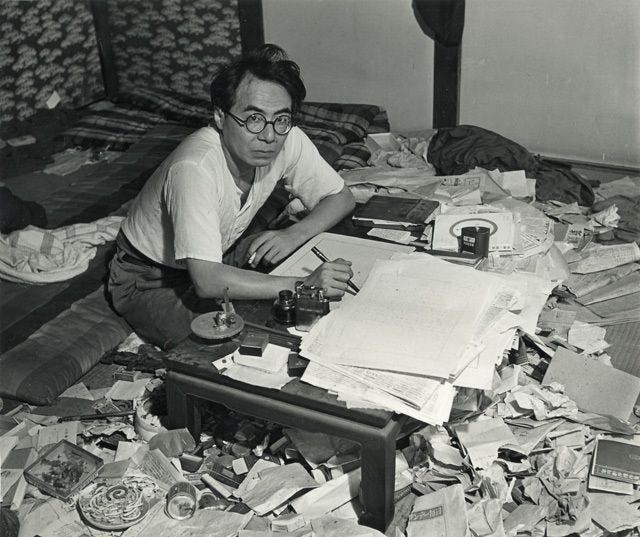

Photo: The writer Sagakuchi Ango, of Japan’s post-war Decadent School, crouched over his low table, surrounded by trash, looking like a madman, which captures, I think, the mood lately (portrait by Ihei Kimura).

Strange days.

I went for a run through our neighbourhood last night, which was no more quiet and comatose than it usually is at 10 pm on a weekday, except that this quietness now seems inflated with purpose; everyone is doing what they typically do — hanging out at home, watching TV — but hyperconscious of it, which often makes reflexive things harder, like thinking too hard about walking, or chewing, or breathing. I caught a glimpse of CNN through the front window of a house; some gray-haired talking head beside a bullet-point list. The church parking lot, which usually has a few mini-vans scattered about no matter the time of day, was completely empty, a wasteland of muddy puddles. Running along one of the main thoroughfares, I saw more cars than I thought I would, but still far less than usual. When I turned the corner back onto our street, I came upon a large rabbit in the middle of the sidewalk. It was doing what rabbits always seem to be doing, just kind of sitting there, assessing the situation, ears twitching towards every sound, and I watched it do this for a while. It let me creep within two or three feet before it scampered away through the hedge. There are often rabbits cruising around our neighbourhood, and it would be foolish to think that after only a couple days of fewer cars on the streets that animals were already reclaiming the spaces we’ve been forced to vacate, but when I got back to the house, a dark shape zipped across our driveway into the neighbour’s yard — another rabbit — and I thought: well, maybe?

/////

Earlier that same evening, on a walk with the kids (we are doing, now, what we always should have been doing after dinner: going for a long walk as a family, which gives me solace that some of the new routines we’ve been forced into are healthy ones), we ran into a neighbour out walking her dog. She works at a fertility clinic — the same one my wife and I once patronized — and she told us that earlier that day they’d suspended operations. She’d spent that afternoon freezing eggs: all those little potential humans that had, after months of drug treatments and surgical procedures, been plucked from troubled ovaries and prepped to take an alternate route into the womb. The fertility clinic is considered a non-essential service, she explained; and besides, they no longer have the equipment they need to perform even the simplest medical task, since all the gloves and facemasks and other things are being diverted to hospitals. Every extraction and implantation has been cancelled. Fertility treatments are long-cons on a underfunctioning reproductive system: there are months and months of consultations and hormone treatments and careful monitoring that precede these procedures, and it all costs tens of thousands of dollars. Being infertile feels like the universe has casually, mindlessly singled you out for suffering — this, I can tell you from experience — so I can’t imagine what it feels like to have your one faint hope nullified by, of all things, a global pandemic. There were tears, our neighbour told us, as the staff shuttered the clinic. Staff and clients alike. And what now, for our neighbour? She is applying for EI. Her husband is retired, so they should be okay for a while. But who knows how long this will last.

This was the longest conversation we’d ever had with this particular neighbour (conducted at a distance of several metres), and she told us all of this with the sort of naked solemnity that is antithetical to the very notion of casual neighbourly chit-chat. But I guess that’s where we are, right now: revealing ourselves to whomever we happen to run into during our allotted time outside of our homes.

/////

I am working on everything and nothing. I’m finding it impossible to focus. I’ve had to turn off the wi-fi on my laptop to prevent myself from mindlessly clicking over to news websites to find out the latest thing (because there’s a new latest thing to find out every ten minutes or so). I’m lucky to be able to keep working, though. For now. What everyone is currently doing — trying to find space within their homes and home-life in which to work — I have been doing for a while, now. These coming weeks and months will be the true test of whether you’re an introvert or extrovert: people will suffer or celebrate this pinpoint narrowing of their contact with others. Me? I’m celebrating, but cautiously. I’m grateful for the limits imposed on my action and attention, and also grateful for the occasional online group hangout (finally, teleconference technology is bringing joy to people’s lives instead of pain).

/////

I made one of my essential trips to the grocery store yesterday. Loblaw’s has barricaded its entrances with stacks of pallets — the sort of makeshift fortification you see in zombie movies — directing customers through a sort of twisting maze to get to the front door. Once inside, there is a handwashing station. After that, it’s all pretty normal, except for the empty shelves where toilet paper and flour are usually displayed. I ended up buying far more than I intended to. Strange things that I hadn’t planned on getting, too: Jell-O, frozen mangos. One’s psychological reaction to scarcity — or perceived scarcity — is a strange thing.

On my way back to the parking lot after checking out, I saw that there was now a line of people outside the store waiting to get in. They were calm, patient. Like this was a totally normal thing, to line up in the parking lot outside a grocery store on a Friday morning. Humans are pretty resilient, I think. We adapt to new circumstances quickly, and the arc of our collective behaviour, despite those few glaring examples of the opposite, will generally curve towards the common good.

Still, I’m less scared of viruses than I am of other people and what even the best of them are capable of doing when they feel threatened.

/////

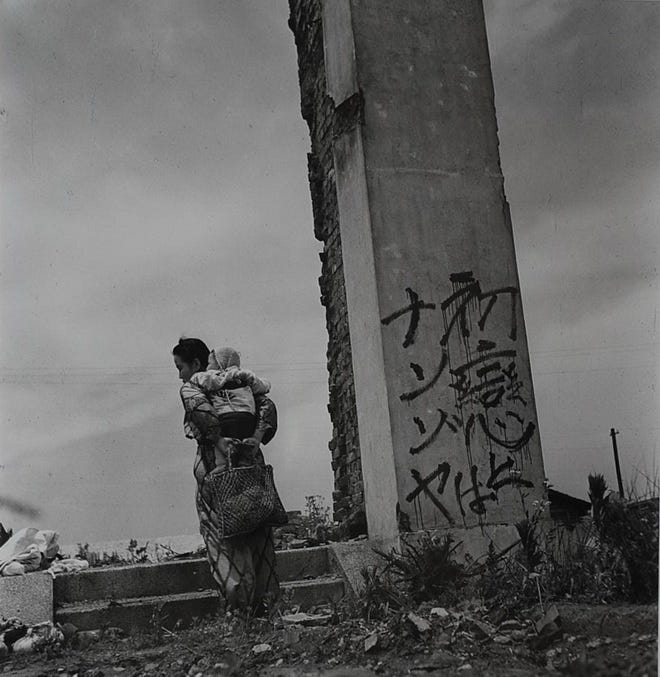

Over the last few months, totally by accident, I’ve become interested in post-war Japan — that once-flourishing society forced to reassess and recondition itself after a crippling event (specifically, the dropping of the Atomic Bomb and subsequent American occupation) — which suddenly seems pretty relevant, don’t you think? In January I went to the Hanran exhibit at the National Gallery, which documented work of Japanese photographers from the period between 1930 and 1990, aka. the Showa Era, which is “remembered in Japan as a tumultuous time, when tradition and modernity converged and Japan emerged a prosperous, industrialized country.” It was one of those transporting experiences, akin to time-travel and ghostly possession, that leaves you feeling as if you’ve briefly lived another life in another place. I discovered Ihei Kimura, Tadahiko Hayashi, and the O.G. perverted grandpa, Nobuyoshi Araki—all of them are worth looking up and reading about. Hayashi’s 1947 photograph “Mother and children in a war devastated area” in particular compelled me, and I stood for a long time looking at it. The composition favors the vastness of the cloudy sky, and the dripping graffiti is straight out of an R-rated post-apocalyptic anime, but it was the ground that for some reason interested me: the details of debris and trash and scrubby plants. In the end, the photo is rather ominous, isn’t it? Perhaps I was sensitive to the coming mood.

As well, in the past month, frustrated by the streaming industry’s endless library of the same old stuff (and by my own paralytic indecision), I signed up for a free trial subscription to MUBI, which is a curated collection of classic and foreign films, similar to Netflix, but with only 30 movies to choose from at any given time, and all of them are good. Right now, there happens to be a retrospective on the Japanese director Yuzo Kawashima. He’s one of the country’s most beloved filmmakers, but virtually unknown in the rest of the world; Japanese cinema’s Gord Downie. I’ve watched a bunch of his stuff, the last little while: Hungry Soul, Sun in the Last Days of the Shogunate, and Our Town, which has a great central performance by Ryutari Tatsumi — an actor who, it seems, has been forgotten by history (I can find virtually no biogrphical information about him, at least not in English) — and which, with its destitute patriarch managing his adorable small children, reminded me a lot of my favourite movie of 2018, Hiorkazu Kore-eda’s Shopflifters. Kawashima’s films are melodramas, operatic, hot and bothered, yet surprisingly sensitive to (and focused on) the struggle of women in a traditionally patriarchal world (Hungry Soul begins with a hysterectomy and passes the Bechdel test within its first five minutes). They’re about change. How people react to new social, political, and indivdual circumstances and standards in a country whose national identity — as well as several of its citires — has been completely obliterated. Kawashima was a hard drinker, and died young at the age of 45, but not before completing an astounding 51 films, which puts him on the list of prolific artists, alongside Cesar Aira and Georges Simenon, who I loathe for their productivity as much as I admire their work.

What lessons are there to be learned from Japan in this period? That change is inevitable. That many of the things we believe collectively to be essential are actually not — that many of our needs are actually wants — and that knowing what to hold tight and what to let go is the real challenge of living through radical social shifts.

/////

Our trip to Greece is off the books, obviously, but with all the preparatory reading I’ve been doing over the past few months I feel like I’ve spent a good deal of time there already. Cold comfort, I guess. But you take whatever comfort you can, right now.

I read Anthony Perrotett’s history of the ancient Olympic Games, The Naked Olympics, Antony Beevor’s book about the German invasion of Crete in World War II, and a short history of the Antikythera Device, which was discovered in a shipwreck off the coast of Rhodes, where we had planned to stay for a portion of our trip. More on these books some other time. For now, I’ll make this one general observation: every national disaster and human failing and unexpected plot twist that looms so large for us here in the present: we’ve been there before. A bunch of times. We like to think that we’re so much more civilized — psychologically, politically, socially — than our ancestors, but we’re not. Getting blackout drunk at a sporting event, starting a brawl with the other side’s supporters? Risking a fatal disease so you can party with your friends? Refusing to accept the truth of an existential threat until its too late? We’ve been doing the same stupid and wonderful (and stupidly wonderful) things since the beginning of recorded history. Lets not think this current moment is unique.

//////

On my runs, these past few nights, I’ve been listening to the new album by The Wknd, which is excellent music for (a) running, (b) the nighttime, and (c) the end of the world as we know it; vaguely apocalyptic bass beats rumbling behind synths and spooky vocals.

/////

I’m grateful for the weather, right now. Spring seems to have come early (I refuse to look ahead at the forecast, lest this illusion is shattered). I’ve opened the window in my office. There are birds outside. The air smells like spring: the back-to-life exhalations of dirt and grass. The noise of traffic is much reduced. Rabbits own the streets at night. We’re so used to knowing exactly what the world will look like a week from now, a month from now, six months from now. We plan it all out. We know exactly what to expect and when to expect it. Booking kids’ summer camps eight months in advance, 30-year mortgages, etc. And now? Not so much. Will the kids be home from school for another two weeks, or two months, or until next September? Will there be flour at the grocery store? Will the grocery store even be open? The future is a blank page, and a blank page is both terrifying and thrilling.